The article below is from our archives. The information or data contained here may not be kept current.

The Art of

Resilient Capital

Planning

for Executive

Compensation,

Estate Planning

and Philanthropy

by Mark Bronfman MBA, CPA*, Sagemark Consulting

Article at a Glance

Business owners are continuously trying to optimize the use of their capital across several parties: the business (e.g., growth capital), their immediate family (e.g., retirement capital) and other stakeholders via long term value sharing (e.g., executive compensation, estate planning and charity). The business owner who optimizes capital is in a better position to grow the business, maintain control over eventual business succession, and proactively transform the lives of those stakeholders that often give life meaning. Get it wrong (which is easy to do given the immense volatility of the typical middle market business) and the business, personal goals, and relationships may suffer.

The author presents a model for Resilient Capital Planning with an emphasis on strategic value sharing for three key stakeholders: (a) key executives of the company via long term executive compensation, (b) legacy planning for children and later generations via estate planning, and (c) philanthropic gifts via charitable planning. The methodology anticipates great uncertainty and emphasizes the use of self-correcting strategies, a strong focus on the owner’s personal values, and full integration across the business and personal parts of the business owner’s financial plan.

As Featured in the Journal of Financial Planning July 2009

In his lighthearted and enlightening book, Stumbling On Happiness, Daniel Gilbert reveals that people have systematic shortcomings that cause us to mismanage our lives. For example, Gilbert claims we generally lack the imagination to envision radically different futures. As the future evolves differently than we expected, too often we feel our lives spin out of control. As a group, business owners share this same inability to “look around corners.” Too often, business owners set forth business plans, personal plans, and value sharing plans with third-party stakeholders that are based entirely on a singular view of the future. This myopic planning style can hurt business owners and the diverse web of employees, families, and charities linked to their continued prosperity. Now, more than ever, business owners need a Resilient Capital Planning model to increase the chance of success in an ever uncertain world.

Let’s take an example. In 2008, there was a dramatic change to the way many business owners approached succession planning. Prior to mid 2008, business owners with solid companies had a wonderful default succession plan: sell to private equity buyers and/or strategic buyers who were hungry for acquisitions. Business valuations were high, capital was plentiful, and mergers of similar businesses were common. Upon a liquidity event, the owner generously shared value with those they cared about (e.g., key talent, family, and/or charity), thereby easily fulfilling their long term planning objectives.

Then came the credit crisis that significantly changed the business environment; valuations plummeted, capital flows tightened, and many traditional business models were called into question. Now, business owners with rigid succession plans based on a straight-line view of the future are in jeopardy as they are forced to handle an unexpected change of events. It does not need to be this way; planning can embrace the unforeseen.

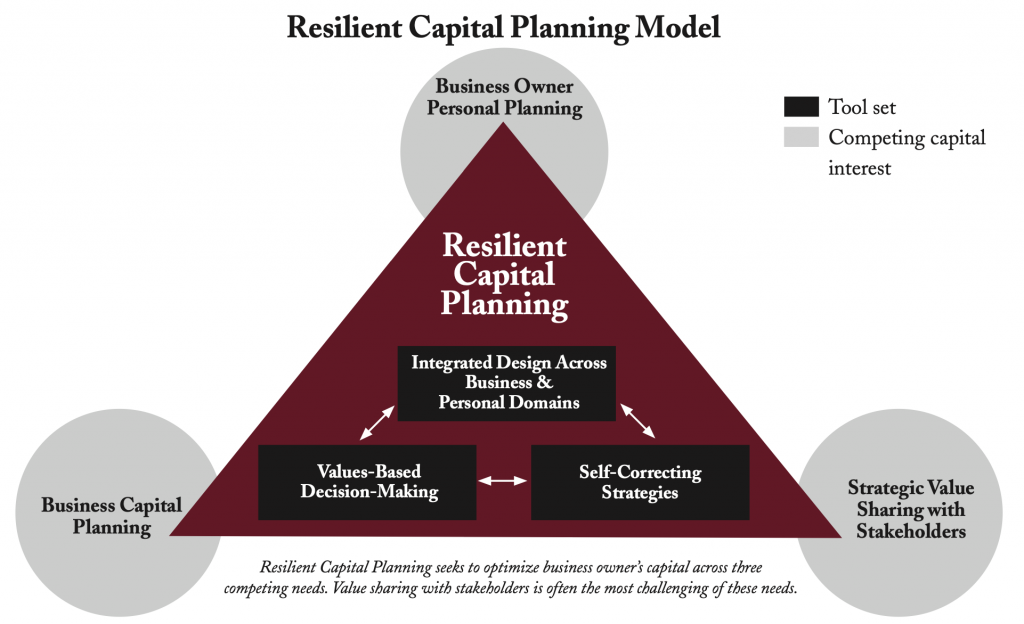

Figure 1: Resilient Capital Planning Model

The Resilient Capital Planning model addresses uncertainty and sets forth a process that self-corrects over time. As illustrated in Figure 1, the heart of the model is an integrated toolset that seeks to balance three competing capital needs related to privately-held businesses: the personal business needs of the owner, the growth capital needs of the business, and the needs of other key stakeholders via strategic value sharing. The model is designed to withstand uncertainty and anticipate the significant volatility inherent in the world of middle market businesses. For many business owners, Resilient Capital Planning can be a foundation of business relationships that last and financial plans that work.

Value Sharing — A Missed Opportunity

Givers gain. Owners who share value with key executives, family, and charity have the opportunity to dramatically strengthen their business and achieve their goals. The benefits of value sharing are significant: greater enterprise growth, enhanced profitability, increased employee loyalty, efficient family wealth transfer, effective business continuation, opportunities for funding social capital, etc. For the business owners, sharing value feels equitable and communicates a shared commitment to success and co-ownership. Strategic value sharing via executive compensation, estate planning, and philanthropy is often the crux of a capital plan for business owners which can transform a rigid, inflexible financial arrangement to a flexible, resilient financial strategy.

Unfortunately, many business owners address value sharing too late in the financial planning cycle. Many wait until they are out of the “business-rich and cash-poor” phase of business ownership – and therefore miss the opportunity to have value sharing empower their business success and hone their personal financial plan.

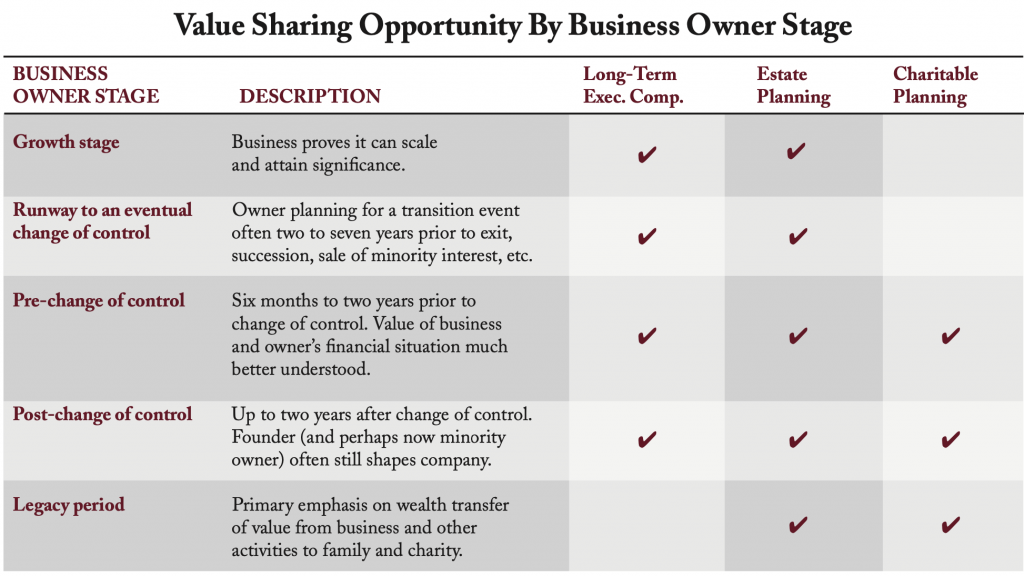

Optimally, value sharing should occur at all stages of the business owner lifecycle. These stages include growth, runway to a change of control, pre-change of control, post-change of control, and legacy (see Figure 2). In the early stages, value sharing with executives is the primary focus as owners seek to supercharge recruiting and retention and reward positive behavior. Furthermore, value sharing with executives can be a key part of laying the foundation for an internal succession strategy, if business continuation is a driving objective. With approximately 40 percent of all business owners reporting that they expect a change of control (e.g., a change of leadership or ownership) within the next ten years, many companies are in this runway stage. (Source: 2007 American Family Business Survey.)

In the pre- and post-change of control phases, the emphasis shifts toward asset preservation. Specifically, value sharing is expressed via family wealth transfer planning related to estate tax and gift tax minimization, asset protection from creditors and divorcing spouses, or family succession planning. In later business owner stages, charitable planning often emerges as an especially satisfying element of the overall financial plan that allows the business owners to benefit from longer-term estate, income tax, and distribution planning gains, in addition to the satisfaction of charitable giving. By considering value sharing opportunities throughout the full business owner life cycle, business owners and their advisors take the first step towards a more complete and meaningful plan.

With the scope of the planning fully considered, the Resilient Capital Planning model can now be applied. The model relies upon three toolsets: the use of self-correcting strategies, the use of values-based decision making, and the use of an integrated design across the various domains of business owner planning. Each of the three elements of the toolset is described below.

Figure 2: Value Sharing Opportunity by Business Owner Stage

Self-Correcting Strategies

Business owners are exposed to risk beyond generic market and environmental risks; privately-held businesses are concentrated assets that are subject to extreme value jolts. Based on the ten-year history of the Volatility Index for smaller public companies (often referred to as the RVX), the value of a typical business enterprise can easily swing up or down by 50 percent within a year. Recently, the credit crunch has exacerbated this volatility, which has lead to especially challenging times for many small and middle market businesses.

Many business owners still put “volatility blinders” on and then fall into the trap of giving (or granting) a significant portion of the company to key employees and family without much forethought related to what happens next. Often these arrangements fail to have appropriate buy-sell covenants, redistribution guidelines, or tax reduction strategies. This giving trap can severely limit the business owner’s flexibility for future equity strategies, such as stock redemptions or sizable cash distributions. In other cases, sudden business environment changes can result in stakeholder disharmony expressed by shareholder disputes, family friction, unnecessary taxes, and unexpected costs. We call the direct sharing of equity ownership a static plan; self-correcting value sharing plans are more powerful and a better fit for most business owners.

Self-correcting strategic design starts by answering the following question: how would a business owner prefer to share value assuming different business growth outcomes? More simply, how would value be shared if the business value over time goes (1) up a lot, (2) up a little, (3) down a little and/or (4) down a lot? For example, a business owner could say that if the business is worth under $10 million, all the value should be reserved for the immediate family. If the business is worth over $10 million, a portion of the value should go to the key executives who helped create value in the company. Above $20 million, an additional portion should be distributed to the rank and file employees who played a part in the firm’s success. Beyond $30 million, some value should be assigned to a charity that supports a cause in which the business owner believes. Essentially, the business owner creates value sharing rules; the higher the return, the more parties are considered for value sharing. Typically, the hurdle for value sharing can be a fixed/nominal threshold (e.g., $20 million) or a variable/risk-based return (e.g., return over the owner’s cost of capital, 20 percent).

Self-correcting strategies incorporate these dynamic rules-based value sharing approaches and tend to have one of four characteristics. One, the business owner shares the upside value rather than granting full equity ownership. When there is a strong equity growth scenario, all parties share the upside; if value falls, the shared value is temporarily “underwater” and the business owner retains the value. Two, the business owner builds incentive arrangements with a vesting schedule or performance unlocks that will control the final transfer of value. Incentive arrangements are the “strings attached” that could cause the recipients to forfeit the value if they separate from the business or fail to meet the performance targets of the business.

Three, synthetic equity can be used to grant business value in the form of long-term compensation rather than true equity. As a compensatory agreement, the business owner can customize the package to address many different dimensions that are difficult to address with a true equity design. And four, the overall plan may reallocate value among different categories of stakeholders (primary owner, key executives, line managers, family, charity, etc.) based on the total amount of value created for the company. This value allocation can occur through the use of what we call “value bands,” which predefine value sharing at various company or owner triggering events. For example, at the change of control in the band of $40 – $50 million, the value going to the owner is $X, the family trust gets $Y, the key executives gets $Z, and so on.

Case Study for Self-Correcting Strategies: Kevin Powers

Meet Kevin Powers. He is the proud owner of the hypothetical Powers LLC, a $40 million publishing firm in the health care industry. Kevin is a happily married, 57 year-old who has fully built out his line management team, but has not yet groomed an internal heir apparent to succeed him as CEO of the business. Kevin is in the runway period of the business owner life cycle; he anticipates a change of control in the next three years – though he is not sure whether he will transfer ownership to his family, to business insiders, or to an external buyer. He is prepared to share business value to attract senior talent and to reward above-average growth, and he is ready to dramatically increase his assets that are shielded from estate transfer taxes. While he likes the idea of sharing value, he wants to retain maximum control and ultimate flexibility for his selected exit strategy. Furthermore, he wants to significantly contribute to his alma mater if, and only if, he and his wife are fully on the road to financial freedom.

Working with an integrated team of business owner planning advisors, Kevin agrees to consider some selfcorrecting value share strategies. For long term executive compensation, he would use a Springing Phantom Stock Bonus Plan in the event of a change of control – giving key employees “skin in the game” without the funding requirements or loss of control that are often a byproduct of traditional plans. For estate purposes, Kevin would sell 30 percent non-voting LLC interest to an Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust for the eventual benefit of his children, thereby removing a significant appreciation value from his estate while maintaining 100 percent voting control. Finally, Kevin would contribute five years of annual gifting to a donor advised fund (DAF) – giving Kevin an immediate tax deduction for the value of the gift. If the business does well, Kevin will continue to add to the donor advised fund; however, if business value declines, Kevin may reduce future additions to the DAF and scale back the future of gifts to his selected charities. In all three cases, the value sharing strategies are self-correcting. If there is limited growth, the executives, family, and charity receive limited value. If there is explosive growth, these same stakeholders benefit greatly. Figure 3 provides greater detail on these self-correcting strategies.

Figure 3 – Examples of Self-Correcting Value Share Plans

Executive Compensation

Springing Phantom Stock Bonus Plan in the Event of Change of Control

How it works: Key non-owner executives qualify to receive a portion (i.e., 5%) of the company value as a compensatory bonus at an eventual change of control.

Why attractive: Owner maintains 100% equity control, plan can trigger value exchange in the event employees leave the company, and the eventual bonus is fully tax deductible to the company at time of payment.

ESTATE PLANNING

Sale of Business Interest to an Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust (“Family Trust”)

How it works: Owner sells minority interest of business to a family trust on an installment sale basis, thereby freezing the value in the owner’s estate (e.g., value of the installment note).

Why attractive: The family trust retains the upside in value beyond FMV at transfer. Strategy is typically self-correcting – if there is significant appreciation, the trust benefits. If there is insignificant appreciation, remaining value in trust may be minimal.

CHARITABLE PLANNING

Multiple Years of Charitable Giving Contributed to a Donor Advised Fund (DAF)

How it works: Owner donates several years of future gifts, typically cash or appreciated assets, in a single year to the DAF; thereafter the donor determines how rapidly to transfer the funds to the charity.

Why attractive: The grantor claims an immediate tax deduction when the DAF is funded and controls the future disposition of funds to the charity. The DAF account may carry the name of the business, which may serve to promote the business as a good corporate citizen. Also, this strategy is easy to scale up or down in future.

The High Five Values Prism

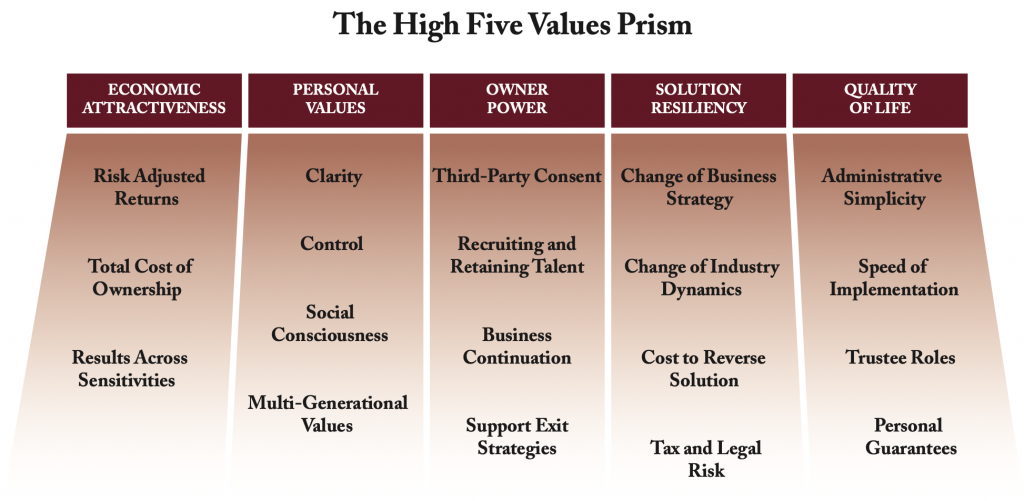

Once the generic self-correcting strategies are selected, the business owner and his/her team of advisors should customize the plan to align with the personal values of the business owner. Each business owner will have a unique set of views (their “prism”) that truly motivate their decisions and shape their design. In our practice, we call our values prism approach “The High Five” as it addresses five critical areas. The High Five explores (1) economic attractiveness – the measure of financial feasibility, (2) personal values – the measure of alignment with the business owner’s tenets, (3) owner power – the measure of leverage attained by the design, (4) solution resiliency – the measure of sustainability, and (5) quality of life – the measure of design independence. A simple High Five values prism is illustrated in Figure 4.

The High Five values prism empowers the business owner to engage in a dialogue about what design characteristics are most relevant for their plan. The business owner can compare candidate design solutions with a standardized set of measurable criteria and discuss their preferences with a working vocabulary. In the end, the business owner will have a more resilient design that closely fits his or her objectives, goals, and passions.

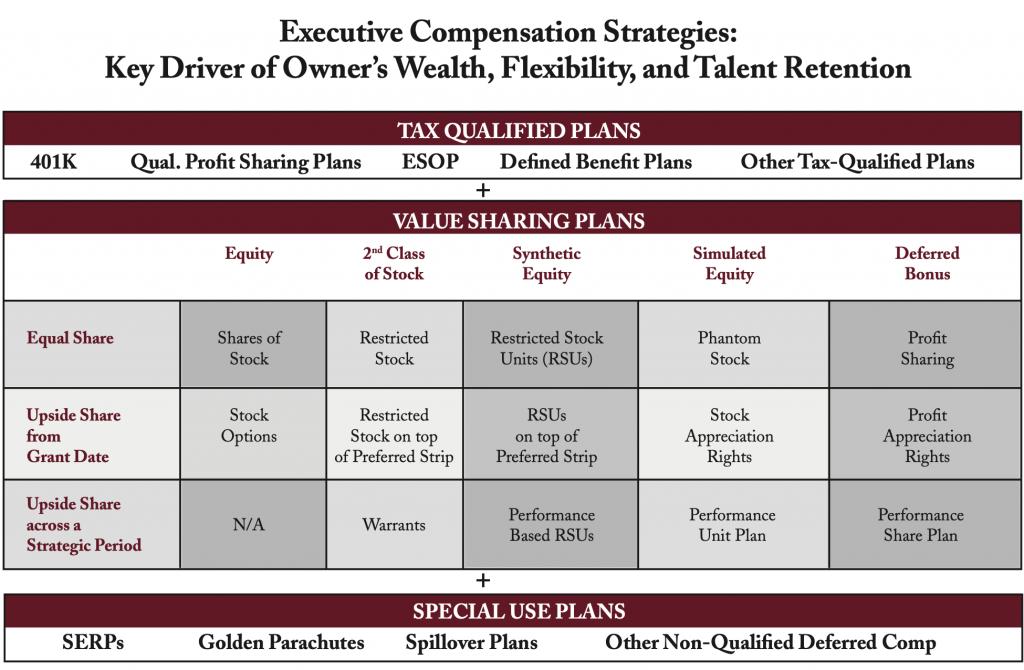

We can use the candidate executive compensation design solutions of Kevin Powers to illustrate the power of The High Five. Kevin is keenly interested in implementing a properly designed long term executive compensation strategy to attract and retain talent and reinforce a common definition of a high performance organization. Kevin’s advisors share a rainbow of value sharing solutions that cover equity sharing, synthetic equity sharing and profit sharing strategies. Our map of alternative long term executive compensation design solutions is presented in Figure 5. Kevin’s advisors discuss the advantages and disadvantages of these solutions given Kevin’s personal priorities and values. The priorities that emerge from the values prism discussion help to balance the three competing capital needs (business capital, personal capital, and third-party stakeholders). Several techniques are blended to anticipate future issues, maximize business performance, and foster human capital harmony. It is through this hypothetical discussion that the Springing Phantom Stock Bonus Plan was selected, as noted earlier.

Figure 4: The High Five Value Prism

The High Five values prism gives Kevin the voice to articulate how he feels about this design. Does it make economic sense? Does the plan feel right given Kevin’s value sharing vision? Does Kevin maintain maximum control and flexibility in the context of value sharing? Is the plan enticing enough to attract an heir apparent? Is the plan founded on strategic principles and “metrics that matter” relevant to his industry for the planning horizon? Is the plan sufficiently simple to implement and maintain? Is the plan designed to withstand volatile changes in his business?

Given Kevin’s answers to these questions, the team continues to make course corrections in the areas of executive compensation and overall financial planning, such as executive compensation trigger provisions and performance incentives, clarity of Kevin’s definition of financial freedom, voting rights for plan candidates, integration of the value share across all of the plans in total, and tax reduction strategies for all related parties. The process is rigorous, well-structured, and clearly defined across the dimensions of Kevin’s financial life, both as a business owner and his role as the patriarch of his family. The plan is self-correcting, values-based, and integrated – it is built to last.

Figure 5: Executive Compensation Strategies

Plan selection can have a dramatic impact on executive behavior, dilution, cost to owners, plan objectives, taxation, plan flexibility, financial reporting requirements, golden handcuffs,

method of plan payout, valuation, change of control and other critical dimensions related to company performance.

Stress-Testing the Grand Plan

Many financial plans for business owners are unfortunately built like stovepipes where business planning, personal planning, and value sharing are each considered separately – and often subject to tepid sensitivity analysis. Peter Schwartz, one of the country’s experts on scenario planning, makes the point that the future is unknowable and often dramatically different than one may expect. Too often people confuse sensitivity analysis (for example, modest changes to a future plan) with what is really needed: a rigorous methodology to stretch our thinking in the face of dramatic future worlds. In The Art of the Long View, Schwartz declares, “Not just our livelihoods, but our souls, are endangered unless we learn to distinguish the significant aspects of the future… By imagining where we are going, we reduce this complexity, this unpredictability which encroaches upon our lives.” This philosophy and practice is central to strategic value sharing within the context of a holistic business owner financial plan.

Consistent with Schwartz’s approach, Kevin Powers and his advisors would imagine dramatically different business and life outcomes to dynamically test the plan. What if my heir apparent leaves to compete with me? What if my children decide they want to enter the business? What if our business morphs dramatically? What if my marriage fails? This process illuminates the strengths and weaknesses in the overall plan, allowing further refinement and reinforcement of the design. By pushing the plan to considerable extremes and addressing exposed gaps, the design has a higher likelihood of long-term success.

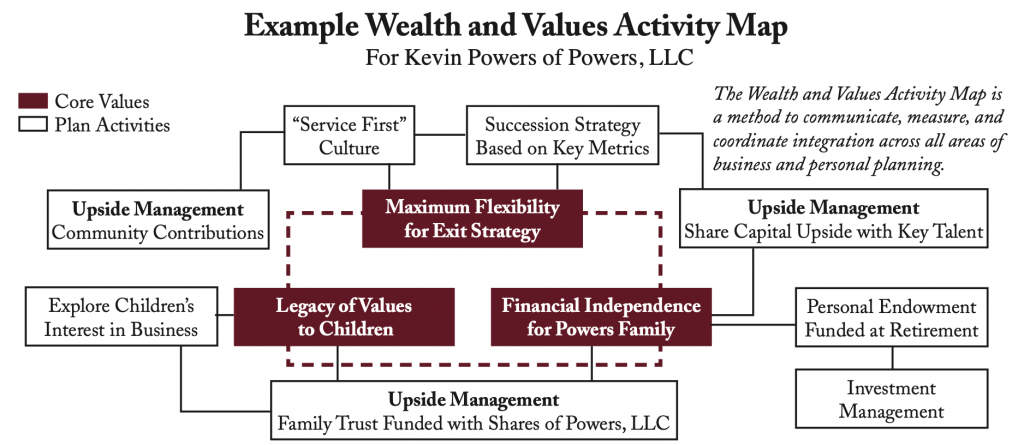

Going forward, a business owner should repeat this envisioning exercise as he or she prepares to cross into the next business owner lifecycle stage (please refer back to Figure 2). By design and intuition, each subsequent stage places less emphasis on business owner planning and a stronger emphasis on personal planning to reflect the realities of the business owner transition. Figure 6 is a Wealth and Values Activity Map for Kevin Powers. This tool illustrates the attractiveness and fit of the overall plan with the key family values of Kevin Powers with many of the planning elements discussed in the case. This holistic plan should be reconsidered, rearticulated, and stress-tested at the transition to each new lifecycle stage.

Figure 6: Example Wealth and Value Activity Map

Conclusion

Ultimately, business owner wealth management is not simply about money in the bank; money matters most when it transforms lives. Business owners are in a unique position to gain value and share value with many stakeholders, starting with their own family and expanding to others via long-term executive compensation, estate planning, and philanthropy.

Business owners and their advisors need a well-defined process to balance the many facets of business owner planning. The process should reflect the changing business owner requirements across the business owner lifecycle. Each of the three capital domains – including the business, the business owner, and the third-party stakeholders – deserves special attention. The scenarios considered should stretch our imagination and take us beyond our comfort zone. The plan itself should be self-correcting and truly values-based. For business owners willing to invest the time and energy in a Resilient Capital Planning process, the rewards can be significant. As one business owner nicely put it, “Resilience, not prophecy, is the greatest gift.”

About the Author

Mark C. Bronfman is a private wealth advisor with Sagemark Consulting in Vienna, Virginia. Mark founded the BOLD Value service line, which is dedicated to the issues of executive compensation, corporate benefits, capital structure, business succession and personal/legacy planning for middle market businesses.

Prior to his affiliation with Sagemark, Mark served as an equity partner with Accenture with a specialty in Strategy and Business Architecture. He earned his MBA from the University of Virginia (Darden) and his B.S. in Accounting from Penn State. Mark is a frequent writer and speaker at industry events and is a non-practicing CPA.

* Licensed, not practicing.

CRN-4663376-040722