The article below is from our archives. The information or data contained here may not be kept current.

Capital

Idea

Crafting a plan

to integrate personal

and family business

capital broadens

an entrepreneur’s

control and flexibility

Capital

Idea

Crafting a plan

to integrate personal

and family business

capital broadens

an entrepreneur’s

control and flexibility

by Mark Bronfman MBA, CPA*, Sagemark Consulting

There is a silent emptiness in the hearts of many successful owners of family-run businesses. They have learned how to make a successful financial living, but not a thriving financial life. Surprisingly, few family business owners have crafted a dynamic longterm capital plan to integrate the enterprise needs of a CEO with the personal needs of the owner of a family business. As a result, the capital at their disposal is underperforming because of lack of focus, integration and strategic intent.

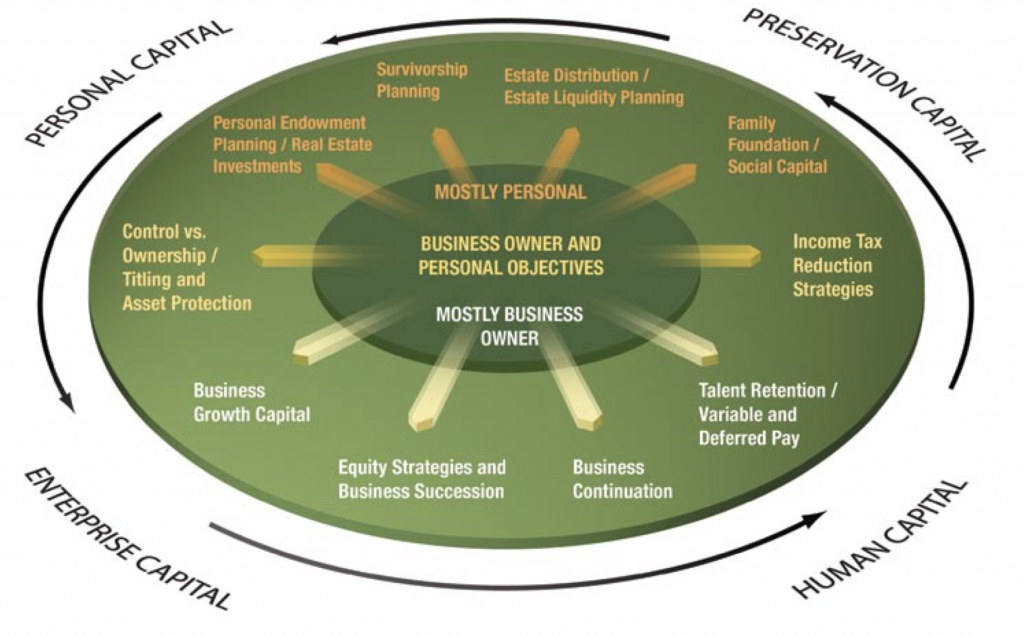

But the capital engine for the family-owned business can be optimized if the business owner integrates, in a strategic manner, the four primary financial capital modules: human, enterprise, personal endowment and preservation. Human capital (investments in people) and enterprise capital (investments in financial assets) are in the business domain. Personal endowment capital (investments for the family’s lifetime) and preservation capital (capital directed for future generations and social capital) are in the personal domain.

When the four capital modules are managed as four independent stovepipes, it is nearly impossible to achieve peak performance. As capital is redeployed and reinvested from module to module, loss of value often occurs because of taxes, capital inflexibility or capital risk. These traps are especially intense for families who are business-rich and cash-poor because every loss of value can worsen their situation.

Traps that often ensnare business owners include:

- Unnecessary dilution of the owner’s equity. We often see owners who give away equity to key employees when simulated equity at a much lower cost would have achieved the same result in talent recruiting and retention.

- Overexposure to estate taxes and personal income taxes at all levels. Many business-rich but cash-poor owners with limited personal assets outside of the business see little need for estate planning—and thus forgo opportunities to transfer significant business value to their family at very reduced values over time.

- Waiting until a major liquidity event occurs to reposition business assets to personal assets. Business owners often miss highly attractive opportunities to reposition business assets to personal assets inside the confines of the business without tax or other frictions. ERISA-based plans or supplementary executive retirement plans are examples.

- Lack of coordination between personal financial planning and enterprise planning, including issues such as charity, investments, taxes, cost of capital and personal endowment planning

As Featured in Worth Magazine October 2006

Figure 1:

To integrate the four capital modules and help drive peak performance, consider employing the following process: clarify the objectives; define and avoid the planning traps; creatively frame an overall straw-man design; assemble an integrated team; and stress test and refine the design until the goals are met. The process works as follows:

- Crisply articulate short-and long-term strategic objectives for the owner and stakeholders. The process spans beyond the business owner to include stakeholders such as partners, key employees, investors, customers and— often the most important stakeholders—the spouse and family. Many facilitation techniques can be good here. Dig deep, and build a strong foundation for planning by understanding objectives.

- Identify the planning traps—wherever they are. The traps often fall between the capital modules, such as insurance capital redeployed from succession planning to estate planning. Use a diagnostic process to explore dozens of bottom-up issues that are critical to top-down business owner wealth strategies. Conduct this planning gap review diligently and periodically.

- Take charge in assembling your team of advisors, and find a true planning quarterback. Many of the capital engine issues fall into an enterprise/personal white space not adequately covered by traditional advisors such as CPAs, attorneys or stockbrokers. Furthermore, often there is no single advisor responsible for taking a bird’s-eye view of the family’s long-term objectives and the related coordination of the plan. Increasingly, business owners can find business-owner wealth strategists who can quarterback the team. Seek them out and take control.

- Stress test the design. It is important to often consider possible extreme outcomes to stress test a plan. For example, how does the plan work if the business continues to be a cash cow with only moderate company valuation? What if the company requires cash infusion to evolve to be a growth story with the prospect of a higher valuation? What safety nets are in place if the business performance begins to weaken? How effective is the “share the upside with succession talent” strategy if the company can evolve to a rocket with high cash flow and higher business value? This process can be very effective in clarifying the expected payoff from certain strategies. Specifically, the process separates out robust strategies (positive or neutral outcomes across the scenarios) from contingent strategies (with positive or possibly negative outcomes across the scenarios.)

Here’s a hypothetical case study that puts it all together. Doug Smyth, 58, owns 100 percent of Smyth Architectural Services, an organization with $38 million in sales that is valued at $15 million. Smyth has significant cash buildup in the company, and, to an outsider, he appears completely successful. However, he cannot figure out how his limited capital can serve multiple masters. His capital needs appear to be overwhelming and include golden-handcuff capital to lock up his non-family heir apparent, shock-absorber business capital to withstand the next business down cycle, personal endowment retirement capital and preservation capital for family business succession and related estate and charitable needs. Smyth is tied up in knots.

Enter the integrated team. They focus on multigenerational planning, investments, insurance and employee benefits, as well as provide access to an outside CFO-for-hire to coordinate financial systems and his business portfolio. As appropriate, capital is positioned to serve double or even triple duty via techniques such as a partial business sale to an IDIT, deferred bonus plans tied to enterprise value and holistic investment plans spanning personal and business risk. A single unified plan is stress tested based on extreme business scenarios. Smyth is fully engaged and chooses to implement only those strategies that are robust, that is, strategies that result in positive or, at worst, neutral outcomes across the plan scenarios. He chooses to delay implementation of contingent strategies. The plan helps provide clarity of definition, purpose and action consistent with Smyth’s priorities.

When completed, a well-constructed capital plan for the family business will address the personal needs of an owner, the enterprise needs of a CEO and the planning gaps in between. The prize from integrated planning: empowerment replaces the silent emptiness. That is a big win.

These traps are especially intense for families who are business-rich and cash-poor because every loss can worsen their situation.

About the Author

Mark C. Bronfman is a private wealth advisor with Sagemark Consulting in Vienna, Virginia. Mark founded the BOLD Value service line, which is dedicated to the issues of executive compensation, corporate benefits, capital structure, business succession and personal/legacy planning for middle market businesses.

Prior to his affiliation with Sagemark, Mark served as an equity partner with Accenture with a specialty in Strategy and Business Architecture. He earned his MBA from the University of Virginia (Darden) and his B.S. in Accounting from Penn State. Mark is a frequent writer and speaker at industry events and is a non-practicing CPA.

* Licensed, not practicing.

CRN201304-2079232